Always a home

March 11, 2021

It was the 16th of December — a frigid evening in late 1891. Reverend Daniel Jenkins was walking along the streets of Charleston when he came across four young boys. Alone and cold, with no parent or adult in sight. Abandoned.

“At that time, there was no place for homeless African American children. There was one orphan house in Charleston but it was during the time where people were still segregated, so he took the children home with him,” Mildred Hudson, the executive director of Jenkins Youth and Family Village said.

Despite having children of his own, Jenkins decided to take the orphans home with

him, a simple act of kindness that paved the way for the establishment of Jenkins Orphanage.

Jenkins met with the mayor and the city council and told them about needing a place for children so he could help keep them off the streets. The city of Charleston gave Jenkins a place to keep the children and about $100.

“They were glad to know someone was interested in keeping these children off the streets,” Hudson said.

And thus began the legacy left by Jenkins in the Charleston community that still exists today — reaching and impacting the lives of families and children every day.

Jenkins had been born into slavery, but was emancipated right before the end of the Civil War. He then married his wife Lena James, and though Jenkins and his wife were not of great financial standing, Jenkins still took the abandoned children into his home and cared for them when it seemed no one else would.

“Jenkins believed that the meeting was not a random event – he felt that he had been chosen for a higher purpose; to be a missionary to the thousands of unwanted black children who had been left out of Charleston’s system of public care,” James Hutchinson on the Jenkins Youth and Family Village website said.

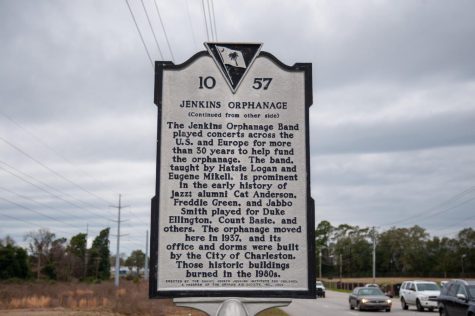

The first place the orphanage took roots was in downtown Charleston. Jenkins wanted to help found an organization that would help all black orphans, which he finally did over the course of the year when he received a charter from the state to operate an Orphan Aid Society.

“The first site was 660 King Street and he got with his church members, ‘cause he pastored at a church downtown, and they decided to organize a home, then called the organization the Orphan Aid Society and in July of 1892 it was incorporated,” Hudson said.

Later the organization was moved down the street, 7 minutes away.

“They moved him to Franklin Street, 20 Franklin Street and … the orphan home stayed there till about 1938,” Hudson said, “actually in 1937 there was a fire and it was the year that Reverend Jenkins passed away, so his widow met with city officials about finding a place for them and that’s when they moved the home to the site where it is now on [3923] Azalea Drive.”

Not only did Jenkins take in homeless children, but he also sought to reach and reform kids who found themselves in trouble with the law. He understood the desperate measures they had taken to survive and wanted to help them, not punish them.

“Not only did he house homeless children, he used to go to the court because a lot of kids survived on the street by stealing,” Hudson said, “so when they got caught, they had to go to court, and the jud

ge would send them to what they call back then Reformatory School. So he would go to court and ask the judge to place the children in his care and they did. And at one time he had over 360 children in his care.”

Jenkins was committed to helping the children in the community as much as he could. The organization’s website mentions how the local papers deemed him “the Orphanage Man” and he became known as Reverend Jenkins or “the Parson” in reference to his saint-like selfless actions helping unwanted black children throughout Charleston.

“He hired teachers and people with other skills in the community to teach the children a trade so that when they were able to leave the home, they would be equipped to work, find gainful employment,” Hudson said.

But in order to sustain the home for the children, Jenkins required funding. The creative solution he came up with is often regarded as the trademark of Jenkins Orphanage, the Jenkins Orphanage Band. Jenkins took his musical talents and put them to use, organizing a band with a few of the orphan kids and taking their talents to the streets.

“They started playing on the streets of Charleston with the permission of the city mayor and so they got money for that, and several people heard them and requested them, so they began to tour the United States as well as Europe and that’s how he made money to keep the Orphan home going,” Hudson said.

Incorporating the traditional African-American music in Charleston, the band paid tribute to black artists and their influence over Charleston culture through their musical performances. The band rose in popularity throughout America and Europe, playing on street corners, in churches, in nightclubs and anywhere else ears were within reach.

“The band developed several rituals that endeared them to their white neighbors back in Charleston. One was to stop their bus two or three blocks away from the orphanage when returning from a road trip and to march in the rest of the way, triumphant, while lines of white children followed them, puppy – like and adoring,” Hutchinson said.

Though the band eventually died out due to a shift in priorities–children attending school and getting an education–the band’s legacy still lives on. Its influence over the community was immense and though the band no longer plays, Jenkins Youth and Family Village still impacts the community in a multitude of different ways.

Over the years since its founding, Jenkins’ institution has evolved and adapted with the constantly changing times. When the orphanage first started out, many parents would drop their kids off and then pick them up later, but oftentimes parents didn’t return and the children were left orphans. As the Social Welfare Agency began to take over orphan homes in the United States, the numbers within the orphanage dwindled as the laws regarding child abandonment became stricter.

“Jenkins became licensed as a level one group home and housed children with very little problems as well as children unable to function well in a foster home. Children were placed in foster care because of abuse, neglect and/or abandonment,” Hudson said.

As the years progressed, the dynamic within the orphanage shifted. At first it was all boys, then it became boys and girls and today it is all girls, mainly between the ages of 11 and 18, sometimes up to 21.

Jenkins provides many programs for the people placed in their care. Jenkins was funded by the Department of Education to provide an after school tutoring program along with other educational programs aimed to prepare its students for becoming successful members of society.

“We also had incorporated a transitional program for the older girls so we could prepare them, when they leave they can either go to college or become career oriented and with the hopes of them finding gainful employment and we had quite a bit of success in that area,” Hudson said.

Jenkins Youth and Family Village, as it is now called, has seen many of these programs succeed and they have had many girls leave and go to college or find employment with the help of scholarships and other financial aid opportunities provided by the organization.

But Jenkins’ influence is not limited to those a part of the organization, it also reaches to people within the community.

“The community was always well involved with Jenkins,” Hudson said. “The children went to school and we allowed them to have their friends visit as well as visit them themselves, their friends from school. And we would have activities out here that would involve the community…Parents, children would come over, sometimes they would bring their donations and the kids would stay for awhile and play … our relationship with the community has always been good, especially getting that financial support to help the institution maintain its programs.”

Today Jenkins still maintains its community support and continues to involve and partner with other community organizations in an effort to offer and make available additional programs as well as maintain parent involvement.

“We had to kind of suspend them for a while because of COVID, but we hope to resume and we’re partnering with other organizations that will provide programs once we are able to open the campus back up again,” Hudson said. “We’re planning to become an independent living site so th

at we’ll have the girls come in — and most of them should be finished [with] school, they may be working, but the goal is to put them in transitional programs and help them prepare, so that when they decide to leave…they will be able to take care of themselves and not be a burden or hardship on the community.”

Jenkins is focused on its goal in helping the people within the program become good citizens in the many programs and real world situations and simulations they provide.

“They had to prepare resumes, do mock interviews for jobs and we would take them out into the community. We took them on college tours at least twice a year,” Hudson said, “then we partnered with other groups who’d let the girls shadow them on the job, so they could kind of get an idea what it’s like, you know, when you’re on your own, what it’s like to be on the job, what you need to do — so we taught them a lot of things.”

As the Jenkins Youth and Family Village evolves and grows in its programs and aspirations for the community, it is experiencing a name change, though the goal of the organization remains the same — help children and families within the Charleston community.

“We’re still Orphan Aid Society, we’re now doing business as Jenkins Youth and Family Village and that will incorporate all the programs that we are working on now, the independent living, the educational programs for the children in the community as well as transitional programs, also we want to involve parents and we’re looking at possibly female veteran program,” Hudson said. “So, it’s gonna not be so restricted to children, but to families as well. And that’s why we decided to rename it Jenkins Youth and Family Village.”

As the executive director, Hudson has experienced first hand the rewarding feeling of doing good in the community. She knows just how impactful Jenkins Youth and Family Village really is.

“I enjoy it, especially when we had a lot of children here,” she said. “It was good to see that someone would finish the program and they didn’t just walk away to nothing, but they went on to school or they were able to return to their family, get that support and they had jobs.”

And the organization isn’t done yet.

“We have some dreams for the future and we want to get started and as soon as we can,” Hudson said. “We’re gonna do our best to bring some of those things to fruition so that we can have the opportunities and everything right here for the girls — not only just the girls but the children in the community. We want them to look at where they are and see where they can go, set their goals and do what it takes to get there, take the necessary steps required to obtain that goal.”

As the Charleston community has had to grow and evolve, so have the things that make it what it is today, like the legacy left behind from a kind man all of those years ago. From Reverend Daniel Jenkins, to the establishment of Jenkins Orphanage, to what is now Jenkins Youth and Family Village — the organization’s impact on the community and its central goal of doing good has remained constant.

us Sunnah Foundation • Mar 15, 2021 at 2:34 AM

Brothers and sisters…

Let’s help orphans and needy people in Indonesia with us

Please support us at ussunnah.org/orphans