The silent epidemic

January 29, 2021

That relief.

That sweet, sweet relief.

It crashes over you as the effects kick in — the world becomes a delicate haze of tranquility and there’s nothing to worry about anymore.

Bure bliss.

Each time the feeling lasts shorter and shorter, when it fades, you take another. You check the label to make sure you’re not mixing anything up. “Oxycodone” it reads, and you laugh at how the letters float around on the bottle — and you take the next dose.

Enough time passes and you subconsciously reach for your next high, when you realize there’s nothing left to take.

Panic.

Panic as you turn over the books and the nic nacs covering your dresser as you search for something, anything resembling that tiny little pill you take everyday. “It’s harmless,” you tell your friends — something to just keep the edge off when the world seems like it’s caving in on you.

But if it were harmless, why are you tearing apart your room for it? You know it’s not on that dresser, but you turn it over anyways, desperate.

Desperate and scared.

***

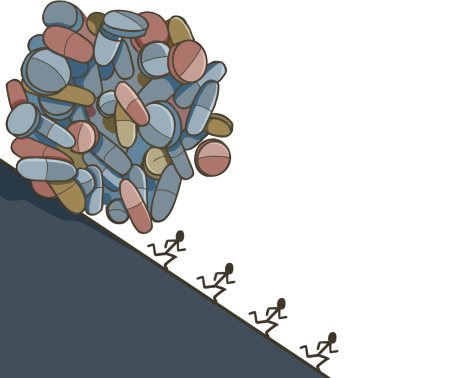

This is the reality for thousands of teenagers on a daily basis. Over 276,000 of them used prescription pain relievers for non medical use in America in 2016. The Opioid Crisis, which began slowly in the late 1990’s when pain relievers such as codeine and oxycodone became more readily available in pharmacies. It has now progressed to the leading cause of accidental deaths in teenagers in America. Why teenagers? Simply put, at a young age, their brains seek out thrills to fuel a dopamine release, and they are unable to make mature decisions on where the line is between healthy thrills and unhealthy thrills. To understand even a glimpse of the complexity of this phenomenon, the stories of those affected need to be told. And not just by past users, but the ones closest to them and the ones that helped them get past their addiction. The sorrows, tragedies, possibilities and triumphs of addiction are all a part of the story, and that’s where we begin.

***

“I was addicted”

“Roxicodone,” anonymous said. “A pain relieving drug.”

Given to them after a broken fibula, the doctor signed the prescription out of protocall for pain. Something he did everyday for all ages of patients with a major surgery — what he didn’t know was this was the start of an addiction.

A “false buzz” is what it’s described as. A buzz that starts to cling to the nerves of the body it enters and makes a statement of disapproval when it feels like it’s being forgotten about.

And this is how it starts.

Most kids would never have tried opioids if they had not been prescribed them for pain in the first place, but the tolerance starts to kick in and those kids start to associate the drug with the feeling of serotonin due to pain going away when they take them.

“My parents knew it was a problem when I would finish my entire dose in half the time it said it would take,” anonymous said. “Basically I was taking double the amount I was supposed to, and that’s when they decided rehab was necessary.”

Six and a half months they were there, focusing on awareness and treatment to help them find alternatives and reasons to not want to dull the life they’ve been given.

Yet, at just fourteen years old, comprehending the degree of how serious this was was difficult. Seeing that brightness at the end seemed like a fairytale people told others to get better, unreachable for them.

“I felt like a monster,” they said. “My mom sent me to Florida to get treatment because she didn’t want me to be near her.”

When on drugs, no matter the age, people are not themselves. The major signs to look for are: irritability, sudden poor academic performance and loss of interest in things they usually love.

But those symptoms didn’t stop anonymous, as they usually would discourage those addicted. Instead, they gave her a reason to stop pretending like they were okay. Those, and the fact that I wanted to be a better older sister. Their step mom being pregnant, they refused to let those pills stop her from sharing moments with a child who could see no bad in them.

“I knew I needed to get help and protect them from everything I have seen,” anonymous said.

And they did.

They got better. They found that one little reason to stay around and take care of themselves, even if they didn’t realize at the time they were doing it for themselves as well.

“I still battle today. Sometimes I think ‘if I have just one more dosage I’ll be okay,’ but it gets easier over time. It’s better than it was two years ago but it’s still hard,” anonymous said.

This is common for almost all recovering addicts. One does not simply quit one day and never feel that itch to buy a pill from someone at school ever again. It’s cliche, but it’s a process that has ups and downs — one just has to remember the feeling of the highs to get through the lows.

***

“My son was addicted”

“He overdosed on heroin,” Nanci Shipman said. “Freshman year of college, days after getting out of rehab, we got the call from people in Columbia [South Carolina] that he was unresponsive, and two days later he passed away.”

Creighton Shipman, a part of the Shipman family who’s been in the Lowcountry for years, was a victim of his addiction.

His struggle was longer than most; it began when he had major surgery for an injury in his ankle from lacrosse, and like many before him, was given opioid painkillers.

And for years he would be addicted, slowly progressing to using heroin for a stronger high — unfortunately supporting the statistic that four out of five people addicted to heroin started with prescription pain meds.

It wasn’t until he was at his worst, a few years later, when his mother went to visit him at college, when she knew something was wrong.

“I can always tell from his belt loops how much he weighs or if anything is off. It must have been a few notches down from where it usually is when I went to see him,” Shipman said.

The most noticeable symptoms of heroin use are major weight loss and sudden poor hygiene, something that family members and friends are the first to notice.

Creighton wanted to get better, though, He “wanted his family back” he told his mother.

“I told him he couldn’t live with us if he wasn’t stopping,” Shipman said. “It’s almost impossible not to feel guilty as a mom.”

Agreeing to go to rehab in an attempt to fix things. He did well. But unfortunately, for many like Creighton, relapses can happen in seconds, just when things are starting to get better.

The deaths of opioid misuse rose 19 percent in one year from 2015-2016.

July of 2016, Creighton was gone.

And nothing could have prepared his family for that.

“If he had not told me he was okay with me sharing his story to help people, I probably wouldn’t be saying this or be doing what I’m doing, but he did,” Shipman said.

What she did was incomprehensible.

Not wanting to watch families suffer from opioid addiction like hers did, she created WakeUp Carolina, a non profit organization in Mount Pleasant that started off as a simple meeting once a week in a police station to now one of the most well known organizations in the south east for recovery advocacy, giving resources to those in need and support to those affected.

“There is a light that people can see,” Shipman explained. “I’m not anyone special, I’m just working with what God or whatever higher being has given me.”

Nanci may not call herself a saint, but taking a situation that could have secluded her from the world for years and instead making sure no other mother has to go through something like that alone is hardly something just anyone could do.

“Addiction is not only bad things. People can get better. We need to focus more on what we can do to help and not shy away from it,” Shipman said.

Shying away from it only makes those addicted feel more alone. Teenagers’s brains are not yet fully developed — the feeling of the “high” they get from these drugs feel more intense at this age as opposed to when they reach their late twenties. It’s because of this, that the longer they are on them, the harder it is to get off of them it is.

It’s when we talk about addiction at an earlier age that we can start seeing a change in how kids approach them. Avoiding education only makes it harder for them to differentiate what their bodies can and can’t handle.

And that’s why people like Nanci Shipman are important — they see this and make it a mission to help these kids — and by doing so, could potentially save lives.

***

“I help the addicted”

“People don’t want to be addicted,” Caitlin Kratz said. “It’s not like they want to be struggling with that shame.”

As the program director for the Charleston Center, which specializes in counseling to recover from opioid addiction, Kratz has seen the process of recovery in almost every way possible — and she is clear on how to help.

“Never play the blame game. That never works. They need to be listened to and reassured that what they’re feeling — guilt, fear, all of it — are all normal.” she said. “Some aren’t always ready to get help but maybe they are ready to talk.”

To her, expecting the one addicted to always come forth is damaging and setting them up for failure — it’s the people around them that need to speak up.

“If you’re worried just say something to them. It’s so important that they know they won’t be judged. Just approach them with care,” Kratz said.

There are always resources — it can be a friend, a community hotline, or even an anonymous outreach email. Kratz and other people in her position realize that every case of addiction is different, but there is never not a way out. Past addicts go on to live long happy lives. They make a family, develop a career, or even go on to help others in recovery — and these outcomes happen every day.

“I had a patient who, after recovery, came to me and said, ‘This is the first time I feel like I’m actually experiencing life. I know what happiness feels like,” Kratz said.

***

Addiction is not the end. People recover every day. Some relapse hundreds of times before they get it right — it’s never linear — but hope is never gone for good. There’s always a way — but family, friends, teachers and bystanders need to be aware of the signs. Of the symptoms. Of the ways to help. Putting recovery all on the addict puts unbearable and unrealistic pressure on someone with a disease — addicts tend to be in denial about their disease and usually refuse to seek help because they are so dependent on the high it gives them. The opioid crisis has taken many lives, but it doesn’t need to continue.